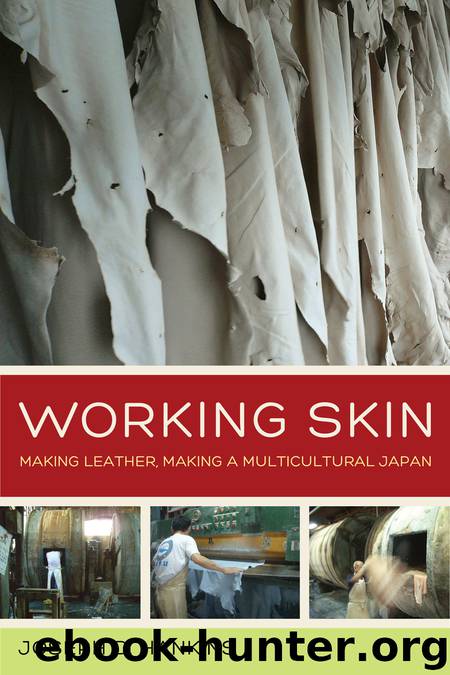

Working Skin by Joseph D. Hankins

Author:Joseph D. Hankins

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780520283282

Publisher: University of California Press

THE INESCAPABLE “YOU” OF DENUNCIATION

While the Buraku liberation movement has utilized public forums since the 1960s, it has used the kyūdankai, or denunciation session, since the early parts of the twentieth century as part of its strategy to eliminate discrimination. Developed with inspiration from Confucian forms of self-critique and consciousness-raising, these denunciations harnessed anger and umbrage to publicly castigate—with screams and brightly colored placards—offending others. Replete with a flair for public drama, these denunciation sessions were to foment the shame of public scrutiny and compel an offender's self-critique. This tactic gained the movement's attention, but as a political presence both forceful and fearsome. It was explicitly based on consciousness-raising techniques, and it carries those overtones into the human rights forum, contrasting with the ideology of this second public. As I outline later, the denunciation tactic expanded and developed over the decades following its inception to form the basis for the current addressed public of the BLL and IMADR, but with a public shaped around demands very different from that of the human rights seminar.

The denunciation sessions were born in an era of political uprising in the region. The Russian Revolution had occurred in 1917; China had seen the Xinhai Revolution in 1911 and the May Fourth Movement in 1917. Within Japan, a similar left-wing and proletarian movement was burgeoning. The Suiheisha formed in 1922, the same year as the formation of the Japanese Communist Party. It was in this broad regional milieu that the Suiheisha developed its first proper political tactic, the denunciation session, explicitly modeled as a technique of self-critique. These sessions were also developed concomitant with a distrust of and a lack of support from the state. In the 1920s, just as now, Japan lacked legislation that prohibited or punished discrimination. With the redrafting of its constitution under the U.S. occupation thirty years later, the government would incorporate an injunction against discrimination: “All of the people are equal under the law and there shall be no discrimination in political, economic, or social relations because of race, creed, sex, social status, or family origin.”31 However, this article was never coupled with actionable legislation, leaving it merely a guideline and not a protective measure, and leaving Japanese citizens in the same place they were at the 1922 birth of the Suiheisha. In explicit reaction against previous state-led movements for Buraku assimilation, with the Suiheisha, the Buraku chose to rely on themselves alone.32

At its first national meeting in 1922, the Suiheisha adopted a resolution to “carry out a thorough denunciation whenever the words Eta or Tokushu Burakumin are used with the will to insult.”33 The denunciation sessions that would follow this decision—1,432 sessions in the next year alone34—were marked by two sets of characteristics. On the one hand, they were marked by independence on the part of Buraku people. Denunciation sessions were to be an antidiscrimination measure conducted by Buraku people themselves. On the other, they were marked by a focus on individual action and intent. This combination of characteristics intensified

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Born to Run: by Christopher McDougall(7132)

The Leavers by Lisa Ko(6950)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5419)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5375)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5202)

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(5188)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4317)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(4197)

Never by Ken Follett(3963)

Goodbye Paradise(3813)

Livewired by David Eagleman(3778)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3403)

A Dictionary of Sociology by Unknown(3088)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3077)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(3039)

Will by Will Smith(2930)

The Club by A.L. Brooks(2929)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2850)

People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory by Dr. Brian Fagan & Nadia Durrani(2740)